There’s a lot of parallels between NFTs and the plastic surgery industry. And to make my case, we’re going to run through the plastic surgery part first.

If you don’t want to read an essay, you can watch this video from Mina Le (God I love her).

But the seed for all of this personally began with a 2019 New Yorker article, “The Age of Instagram Face.” The essay was about Instagram and plastic surgery, how digital perfection was feeding the pursuit of physical editing.

Digital Instagram filters, creating a physical Instagram face.

There was something strange, I said, about the racial aspect of Instagram Face—it was as if the algorithmic tendency to flatten everything into a composite of greatest hits had resulted in a beauty ideal that favored white women capable of manufacturing a look of rootless exoticism. “Absolutely,” Smith said. “We’re talking an overly tan skin tone, a South Asian influence with the brows and eye shape, an African-American influence with the lips, a Caucasian influence with the nose, a cheek structure that is predominantly Native American and Middle Eastern.”

Basically, if the beauty standard of the early 2000s was being white and anorexic, it had shifted into something so far out of the curve of winning the racial genetic lottery.

But who cares about winning. You can just buy your way to the same outcome now!

The rise of plastic surgery was largely enabled by science. Technological improvements had created this new range of procedures, like fillers and injections. They’re easy, they’re less physically intensive than plastic surgery—”[y]ou can go get Botox and then head right back to the office.”

And most importantly, you didn’t have to sell your kidney to get started. When a syringe of filler costs $683, the entry fee to the world of plastic surgery is attainable enough. Call it an investment under “empowering yourself” and “enhancing what you already have.”

But that price only makes sense for the smaller portion of the population with disposable income. And since there’s nothing special about having the thing everyone has, this hefty-but-not-really price tag does an effective job of keeping it as something to want.

It stays a status symbol.

Status symbols, money, lookism—I’d say there’s a lot of parallels here with NFTs.

Let’s start with how NFT collections are usually assembled from a variety of traits. Certain traits are designed to be rarer than others, and these are usually designed to be visible markers of value: gold accessories, a special skin, or even just simply looking put-together.

This setup makes it easy to tell if someone won the lottery from minting or had the funds to buy their way into the ranks.

Sound familiar yet?

But unlike the physical genetic lottery, it’s obviously easier to fine-tune a digital identity to an ideal state.

Because why the fuck not?

(This is a joke, but it’s surreal to have Michael Patryn just tweeting like this, right?)

Since NFTs designs are still rooted in pre-existing social standards of status, this also triggers some subconscious reactions. One way that this manifests is in the undesirable floor, or to be more outright, a racist floor.

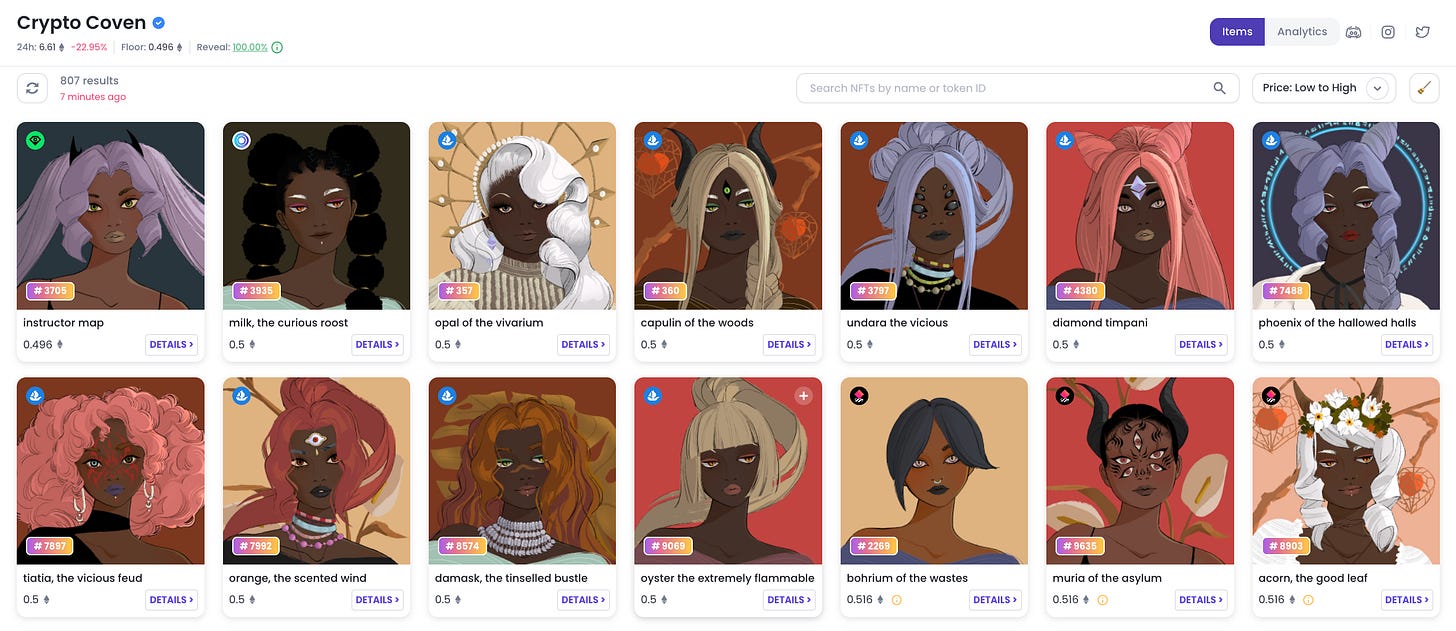

Because for PFP projects based off of people, there really are just some times where the cheapest NFTs are the dark-skinned ones. And it’s nothing but the dark-skinned one.

I take no pleasure in using Crypto Coven as an example, but it was the most visually distinct example I had at the time. Bloomberg’s documented the same thing going on with Cryptopunks, though.

Subjectively, yikes. Objectively, it makes sense to avoid the historical and socioeconomic factors tied to darker skin, but again, yikes.

The financials of all this isn’t great either, so let’s move on because I think I’ve made my point. Societally programmed cherry-picking in NFTs—it exists.

And if that exists, well—what happens after you have picked the thing that you like? Because right now, there is nothing to do but discard one thing for another.

If I tie all these threads together, here is how I see it:

NFTs have facilitated a broad experimentation of cherry-picking identities to align with, as well as the creation of entirely new personas around NFTs.

It was good for the space in its beginning, but we won’t have new people forever. I think certain projects now have communities that have settled into themselves, like the BAYC.

But what happens when the apes get bored of their Bored Apes? One problem is that once you’ve picked an NFT, that’s it, there’s nothing else to do but go and move across to something shinier.

The BAYC brand can’t afford a mass exodus, so it’s why we now have BAYC land and an attempted game, right? Because the real game is to create something so that people never want to leave, but it will take time to develop deeper progression.

I look to plastic surgery for this because the parallels are there. With plastic surgery, there is is that loop of social media creating this look that you could buy into, genetics be damned. The more that people buy into the look, the more people want the look, and so on.

How does that social contagion not remind you of NFTs?

But the difference so far is that plastic surgery is this whole journey. As both essays point out, it does not end with just one visit. There’s always a new flaw to fix, a new procedure to try. There’s always something to attain.

When viewing it as an industry, they just can’t lose. If they somehow can’t get new customers, they can just keep upselling their existing customers by creating new things to be insecure about (insidious, innit?).

NFTs are still missing that depth of choice. But I think we’re getting there.

A lot of this took some nebulous shape during the overlap of two NFT experiences: Anata and Everseed, which were based around identities.

Anata was a collection of easy-to-use VTube 3D models. Their pitch was that it was “the first NFT you can literally be,” as you could “wear” the NFTs on video though facial recognition and motion-capture.

I thought it was a pretty cool concept, especially considering the the percentage of the anonymous population in crypto. It made sense that people might like to appear on videos without revealing themselves.

But, well. There’s some saying that goes like, “Are you wearing your clothes or are your clothes wearing you?”

To me, Anata was not something you wore, it unfortunately wore you. I mean, they were mostly pre-designed models that needed someone to bring them to life. 😅

As fascinated as I was by it, it was still a move across. Going for Anata was to discard what I already had, and that’s not something I want to do (for now).

So compare it with Everseed, which was minting at the same time as Anata. What fascinated me here was how the collection was this collaboration between the project and their users.

At its basic core, it’s really just an avatar creator (with a really good range of features)! Open up any game, and you can find something like the Everseed interface.

But the collection’s randomly generated features were only the clothing and accessories. The people in the NFTs were generated by actual people themselves, using that avatar creator.

It was fun to see what people did with that flexibility. There were some who designed their avatar after their own kids. I had a friend who pursued the “Pinocchio nose.”

People were able to bring themselves into the collection, and not the other way around.

And goddamnit, there’s just something about getting a choice. It was cool to make all those decisions and see the resulting NFT, in my wallet, and know that it was mine.

If you find typos, pls tell me on Twitter.